The Computer/Domino Connection

- A Little Background

- What Are you Talking About, David?

- Some Basic Computational Theory

- The Early Parameters

- the domino has already been knocked down, or

- the domino is just standing there.

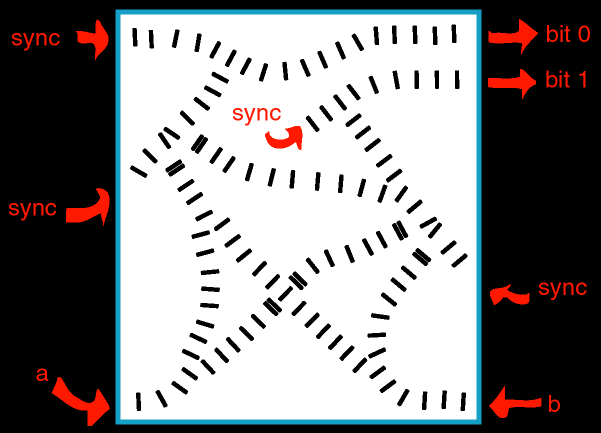

- ...and the Kitchen Sync

- On to More Complex Constructs

- Crossing Paths

- Duplication

- Duplication in Reverse

- Transistor Ho!

- Doing Something (kinda) Useful

- What Good is it All?

- What the Heck is a Single-Bit Adder?

- Various Minor Tidbits

- What Type of Dominoes to Use

- Reliability and Setup Technique

- There's definitely a technique to properly setting up dominoes. There seems to be an optimal distance between two dominoes for reliable knockdown, though I can't say I've quite figured it out yet. If you want near-total reliability in knocking over a domino (such as in a junction or gate), then put two dominoes back-to-back. They'll fall over nice and straight every time.

- When making turns in a line of dominoes, you need to take great care. Dominoes in curves tend to splay out and knock over anything else in the vicinity. I just try to avoid curves when other lines are present. Also, I try to design gates so that things don't need to curve too close to other lines in order to reach them (note the slanted design of the NAND gate).

- Wrapping it All Up

My friend Cory and I were sitting around one day, as we often do, contemplating the mysteries of the universe, when one of us brought up the possibility of building digital logic using only dominoes. We did a web search, figuring that someone must have done something like that before, but guess what? Nary a page was to be found. Cory immediately made a trip the local toy store and bought a package of faux ivory dominoes, and we began work.

Well may you ask what I'm talking about. Well, it turns out that just about anything can act as a computer. In A. K. Dewdney's book The Tinkertoy Computer and Other Machinations, Dewdney says, "Almost any form of matter may be organized into a computer. You can use tinkertoys, ropes and pulleys, even individual molecules."(p. 2) So the thought came to us that it must be possible to make a computer out of dominoes. But how?

Electronic computers (like the one you are using to view this page) are made up of lots of ones and zeros. You've probably heard that before, so I'll go further. A one is represented by an electrical charge, and a zero is the lack of an electrical charge. The ones and zeros aren't the things that do the actual work in a computer, though. What do the computation are little switches that take two signals (each signal is either a one or a zero) and turn them into a new signal based on their values.

The most common way to do this (I don't know of any computers that use any other ways...) is with a transistor. A transistor's output is zero if and only if both inputs are one. With this one simple thing (arranged in appropriate order), it is possible to create a computer that will calculate anything that's calculable.

| input | output | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

These concepts can be applied to any system where you can build a workalike of the transistor. The function that the transistor performs is called NAND (because it is the negation of the and function). The table on the left shows the input and output of NAND.

The first task was to define the most basic parameters of digital dominoes. More specifially, how are the ones and zeros represented by dominoes? Our solution was to say that a knocked-over domino should represent a one, and a standing domino should represent a zero. This was a completely arbitrary choice, and could have been the other way around without changing much.

An interesting problem that we ran into after extrapolating on that idea a little was this: How do you make a domino do something to another domino if

This is a problem because in order to simulate a transistor, we have to make two zeros turn into a one. How do you make a domino fall over if the source dominoes are just sitting there?

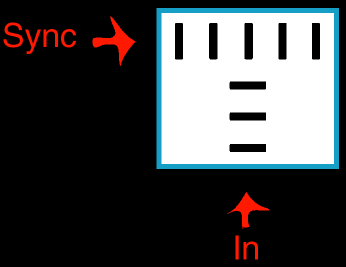

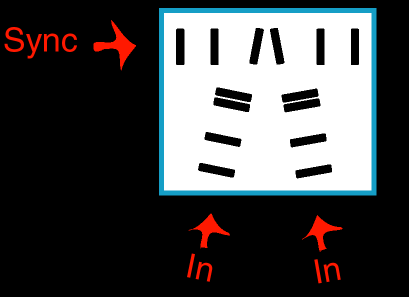

Our solution was to create what we call a sync signal. This is basically a line of dominoes that is constantly falling down (so it is a guaranteed 1). When you need to turn a zero into a one, simply send the sync signal there and use it as your "power source." So in order to create a simple negation, we just needed to have the incoming line knock a domino sideways from the sync line so that the signal can't get through. Thus a one (a knocked-over domino) produces a zero (the sync doesn't get through), and a zero (standing) creates a one (the sync can get through). Here is a diagram of our negation circuit:

In our applications so far, we've foregone the difficulty of actually timing out a sync signal. We've simply knocked over the sync signal by hand whenever it's needed.

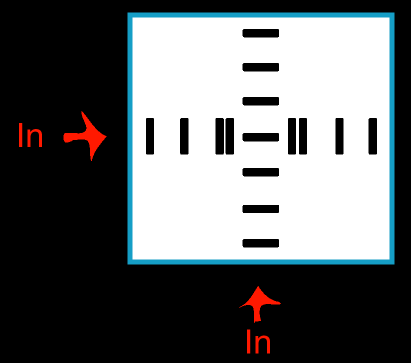

One problem that we faced early on in our experimentation was that of crossing two signals. In transistor-based computers, this has long been a problem. I believe the current record for crossing two signals in a single-plane environment without destroying them is something like 14 transistors. Now in working with dominoes, we have greater flexibility than with transistors. The various arrangements of dominoes we can create hold great possibilities beyond a simple NAND gate. After some experimentation, we came up with the following arrangement to cross paths:

This construct is pretty straightforward, though id does have a bit of a twist. Suppose a signal passes through the vertical line first. Then the horizontal line is still close enough to itself to carry a signal (since the doubles are placed very close to the vertical line). If the horizontal line goes through first, it knocks the middle domino sideways. The domino stays semi-erect, though, susspended between the two fallen doubles. The vertical signal then easily propegates through this construction.

Note:

The fact that those dominoes are doubled up has a purpose. They are placed like that because the doubled dominoes fall in a much more predictable and orderly manner than if they were alone. They almost always fall straight forward, missing the other pieces along the side. Further, they are slightly harder to knock over -- i.e. they need a little more force to move their collective mass. This makes it even less likely that an errant domino will screw up the whole junction. It's often a good idea to have doubled-up dominoes at junctions. I've only included them in this document, though, where I feel that they're absolutely necessary.

A relatively simple problem is that of duplicating a signal. As anyone who's ever played with dominoes can tell you, a Y formation is a simple way to have a single line of dominoes knock down two others. I won't bother with a picture on this one -- I think you can probably figure it out.

| input | output | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| input | output | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

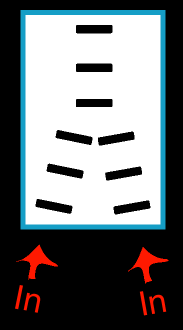

This gate works because if one domino is knocked out of the sync line by one of the incoming lines then the sync line can still get through. But if both are knocked out then the sync line can't reach its next piece, and so will produce a zero (standing).

A fairly important part of this construct, in terms of reliability, is the fact that the incoming lines are slanted. As I'll mention later, curved lines of dominoes are dangerous, especially in the vicinity of other standing dominoes. With the incoming dominoes being slanted like this, though, the incoming dominoes doesn't have to curve to get in line with each other.

This construct actually led to the current design for the NOT gate (See above). The previous design for that was a variant on the Y formation of the OR and duplication gates.

So, you ask me, what good is all this? Well, almost not at all, to be honest. Perhaps it's an un-intimidating introduction to binary logic? (I would probably need to do a little more revision to make it truly approachable, though...)

But, like I said, it is possible to make a full-fledged computer out of this stuff. It would be extremely slow and totally useless, but massively cool at the same time. To demonstrate this, I'll show you a small application of domino digital logic. I'll create a single-bit adder entirely out of dominoes!

Adding two numbers is pretty easy, when the numbers can only be one or zero. In fact, we can whip up a table of all the possible results in a snap:

| input | binary output | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | bit 1 | bit 0 |

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

Well, gee, what we need now is two functions: one that produces the first column of the output, and the other that produces the second column. Well, the first column is easy. It's a simple AND operation, which is the same thing as NOT NAND. So we can make that result easily from the input. The second column is the same thing as exclusive OR, or XOR. XOR is a function that outputs a one if one of the inputs is one, but zero if both are ones or both are zeros:

| input | output | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

This can also be expressed as (a OR b) AND NOT (a AND b), or when we break it down a little, NOT ((a OR b) NAND (a NAND b)). So what we need to make the XOR is a NOT, an OR, and two NANDs.

Furthermore, since we're already calculating a NAND b as part of finding a XOR b, we can simply invert that value to get the a AND b that we need for the first output column. As far as I know it, that's as compact as we can get things, though I'd love to hear from you if you think I'm wrong (that goes for this whole page, BTW). All in all, our efforts yield the following behemoth:

There are a few things that need to be mentioned before you go off and make your own domino computers.

We've encountered some troubles in finding the ideal dominoes. You may remember dominoes from the days of your youth as friendly, uniformly shaped pieces of hardwood. Well, lemme tell ya, you can kiss those days goodbye.

Well, maybe I'm overstating things a bit. In our trips to various toy stores (including Toys "R" Us and Kay-Bee Toys among others), we found only one brand of Dominoes. Oh, the packages looked slightly different in each store, with a different brand name, but they all held the same thing.

The most predominant type was made of plastic. It came in packages of between 25 and 150 (approximately), costing between $5 and $20 per package. They're made of hard off-white plastic that looks and feels like ivory. They seem pretty nice, but the dominoes are annoyingly non-uniform. They stand with varying stability since they vary in both thickness and roundedness.

The other type we found was (I think) made by the same company. They are made of wood and are smaller and even less uniform. Half of them won't even stand on their ends reliably. That's fine and good if one wants to play a game of dominoes, but what about us folks who want to play with dominoes? Huh?

Actually, I tell a lie. I did find one other sort of domino. I found an errant add-on set for an old game called Domino Rally. I couldn't pass it up, since it had 50 dominoes for $3. Well, they turned out to be pretty much useless to me, since they were so light that they fell in a completely out-of-control manner. A perfectly normal line of dominoes wouldn't fall past the third or fourth piece!

Overall, I'd suggest using the heaviest, most uniform dominoes you can. I haven't had a chance to try some good old-fashioned wooden dominoes, but I would guess that they would suffice. Even better, though, is dominoes made of hard plastic, ivory, or even stone or metal. They have good inertia as well as nice firm collisions (think billiard balls).

You have now seen the sum total of the world's information on domino computing. As far as I know, this is the first time anyone has written about this subject, though I have little doubt that it's been done before. I mean, if John Conway simulated life on top of a Go board, then I'm sure someone has done this before.

I'm very interested in your comments on this page. Please email me if you have anything to say.

|

This page is part of the Jone/Stone Information Repository Last updated on November 18th, 1999 Access statistics provided by This page and its contents are copyright ©1999 by David Johnston |